When one searches on Google’s search page, the Chinese words and phrases can strung together without separation, just as in normal writing. What isn’t immediately obvious is that it looks like behind the scenes Google has taken the Chinese pages it crawls and segments the texts into individual words before storing the terms in its database. For example, in Google’s search of web pages, the term 中国 reports over 1 billion hits. With the same term in quotes to indicate an exact phrase, “中国” reports 5 billion hits (with the discrepancy hard to explain). However, when a space is inserted into the word, the exact phrase “中 国” reports 4.3 million pages, which is 0.08% of the amount for the single word “中国”. The kinds of pages returned from the space-separated query include matches for: 中國 in traditional script (for unknown reasons); words separated by punctuation, especially “中(国)” and “中。国” (i.e., one sentence ends with 中 and the next sentence starts with 国); and pages where every character is separated, as if the page were encoded or decoded incorrectly. These results suggest that Google treats Chinese searches the same as other languages, by storing pages in its back end database indexed by the individual words in the page. Storing the terms this way allows Google to quickly return results for a variety of queries, whether the user wants the terms anywhere in the page or as a connected phrase.

Unlike Western languages, you can enter a phrase as a continuous string of unseparated characters and not worry about where the individual words begin and end. For the queries to work, Google must be separating these strings into individual words and then doing the query on these separate terms. As a user, typical search queries generally do what you want, and Google’s internal search algorithms aren’t of concern. If you search for 隐形眼镜 [yǐnxíng yǎnjìng – contact lenses], the 17.5 million results do all contain 隐形眼镜, despite the resulting pages having the characters embedded within long strings of characters. While the majority of resulting hits are exactly 隐形眼镜, there are also results for 隐形透视眼镜 [yǐnxíng tòushì yǎnjìng, contact lenses/x-ray specs(?)], and other pages which contain both 隐形 and 眼镜 as terms but not adjacent. Thus, Google Search seems to be splitting the original phrase into individual words and searching on both. Putting the term in quotes will force a search for the exact phrase. Searching for “隐形眼镜” yields 16.6 million hits, a slightly smaller result due to the filtering out of 隐形透视眼镜 and other words.

You can force Google’s hand and tell it how you want the characters segmented into words. A search for “隐形 眼镜” or “隐形+眼镜” also reports 16.6 million hits, the same number as the terms without the space. In this case, Google already knows where the separation between the two words is, so nothing is being added to the query. If you get the word segmentation wrong, Google still finds some number of pages, but the results are generally a motley assortment of miscellaneous text. A search for “隐+形眼镜” reports 82,000 hits (0.5% vs. the correct segmentation), and many of the pages contain phrases like “隐/形眼镜”, “隐.形.眼镜”, and the like, where extra punctuation seems to have sneaked into the text. Similarly, “隐形眼+镜” reports 310,000 results, with phrases such as “隐形眼-镜”.

| Term | Google Search web hits |

|---|---|

| 隐形眼镜 | 17,400,000 |

| 隐形 眼镜 | 15,200,000 |

| “隐形眼镜” | 16,600,000 |

| “隐形 眼镜” | 16,600,000 |

| “隐 形眼镜” | 82,300 |

| “隐形眼 镜” | 310,000 |

| “隐形透视眼镜” | 577,000 |

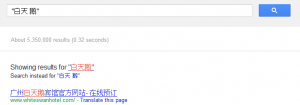

I don’t know what advantage there would be in forcing word segmentation in Google Search. Google has already segmented the words in its back end database, and presumably it is using the same algorithm on the front end. Splitting a term like 隐形眼镜 is straightforward. However, say you have a desire to search for “白天 鹅”, adding a space to specify you want to find a 白天 + 鹅 daytime goose instead of a 白 + 天鹅 white swan. Google’s initial response is to assume you really didn’t mean to do that, and kindly removes the space, defaulting to 白天鹅, which is essentially the same as 白 + 天鹅 white swan. It does offer the choice to search explicitly for your original phrase. The results of that search are a mixed bag, as many of the results are still white swans. However, some of the results are indeed for “daytime geese”, where the writer has specifically added punctuation as in “ 白天”鹅 or 白天“鹅”.1

Hazards of Google Search with Chinese and Wildcards

In Google Search, the asterisk * can be used as a placeholder for one or more words in a search phrase. For example, searching * and chips returns not just “fish and chips” (the top result and most common collocation in English), but “salsa and chips”, “guacamole and chips”, “haddock and chips”, and many other phrases. This is a useful tool for language research or study, as it allows you to explore common and alternative word usage.

The Wildcard search also works for other languages, including Chinese. This can be a useful tool for Chinese learners exploring phrases and grammar. For example, if you weren’t sure of the measure word to use with 手机, you could search for 我买了一*手机 and see what showed up most frequently. The results for the top 50 Google hits are:

| Measure word | Percent of pages in top 50 results |

|---|---|

| 部 | 44% |

| 款 | 23% |

| 台 | 15% |

| 张 | 15% (but only as 一张手机卡 phone card) |

| other | 4% |

Wildcards can be used for many kinds of neat tricks. The 2008 earthquake in China is known as either the Sichuan or Wenchuan earthquake; “2008年*地震” finds them both, plus any other terms that may be used. Or, if you wanted to get ideas for a soup recipe, you could search for “*汤” for a random assortment of possibilities, with the image search being particularly useful.

However, Google has a sort of blind spot specifically for Chinese searches. To illustrate, let’s say we want to see what the most popular ball sports are in China, and search for “*球冠军” (*-ball champion). Here are the terms in the top pages found:

- 乒乓球冠军 (ping pong champion), the predominant result

- 乒球冠军 (ping pong champion)

- 九球冠军 (9-ball champion)

- 马球冠军 (polo champion)

- 高尔夫击球冠军 (golf hitting champion)

- 门球冠军 (croquet champion)

- 健美操花球冠军 (cheerleading/pom-pom champion)

- 板球冠军 (cricket champion)

- 溜溜球冠军 (yo-yo champion)

- 滾球冠军 (lawn bowling champion)

That’s an interesting set of results. It’s no surprise that ping pong is a popular result. But no 篮球 basketball, 棒球 baseball, or 足球 football/soccer? Surely, they should be more popular than yo-yo or lawn bowling!

What is happening is that the wildcard represents a placeholder for additional words, not for completing a single word. This is how it works with other languages as well. In English, for example, a search for “char*” will not return results for “character” or “chart”. Instead it will return phrases in which “char” is the first word in the phrase, and thus the results will include “char broil”, “char grill”, as typical hits.2 Wildcard searches with Chinese words, however, are trickier due to the ambiguity in what defines a word as a searchable term. The results for “*球冠军” can be explained as follows: Google’s segmentation algorithms have determined that 篮球, 棒球, and 足球 are complete words, and do not match a search for “*球”. But 乒乓球 and 九球 are the combination of distinct words 乒乓 + 球 and 九+球, respectively, and do match “*球”. In other words, Google doesn’t consider 乒乓球 or 九球 actual words, at least for the purpose of storing the terms in its search database.

Let’s say you vaguely remember a certain chengyu that means “love at first sight”, and you know it starts off 一见钟 + some character. So you do a Google search for 一见钟* to let the internet fill in the blank. Most of the results are for “一见钟性”, which seems a little off, as that phrase seems more like “sex at first sight”. It’s used as the Chinese translation of a few different movie titles, but not common otherwise. The other results, 一见钟勤, 一见钟晴, and 一见钟秦 don’t seem right either, and they show up in search results primarily as online nicknames in blogs. The real chengyu is “一见钟情”, which doesn’t show up at all in the results. Again, this is because the wildcard doesn’t work within a single word, and Google considers the set phrase 一见钟情 as a single word. The examples that do turn up, 一见钟性 and the others, do so because they mean nothing special in combination, and are probably stored in Google’s keyword database as four separate 1-character words.

Hazards of Google N-Gram Viewer with Chinese Words

Google N-Gram Viewer is a tool to chart the usage of words and phrases over time, in books that have been scanned and converted to text via OCR by the Google Books project. This includes texts in many major languages, including Chinese. The Chinese books that have been scanned go back as far as 1567; however, from this date until 1955 there are less than 4,000 titles. The bulk of the works date from 1956 or later. The Chinese language option in the search interface is for “Chinese (simplified)”, but the data itself contains a mix of traditional and simplified words.3

A while ago, the Sinoglot blog posted about the N-Gram Viewer, giving some example queries to play with. There were many interesting trends in word usage over the years. But some words apparently had no usage at all over the entire time frame, including some very common words like 俄国 [Éguó, Russia], 周恩来 [Zhou Enlai], and 蓝色 [lánsè, blue]. After some experimentation, I found that the N-Gram application doesn’t consider these as single words (1-grams, actually), and adding spaces between characters to make them bigrams (俄 国, 周 恩来, and 蓝 色) is necessary to get graphable results. It’s not clear why such common words would have been segmented in such a manner. The application graciously makes its entire dataset available, and the raw data does confirm that these words really are split this way.

To close with one final experiment, is 蓝色 considered a word in Google Search itself, or does it also segment it into 蓝 + 色, the same as the Books n-gram database does? By comparing the full word versus the word with an intervening space, the reported resulting hits for a few different colors indeed does suggest there is something special about 蓝色 behind the scenes. This can be also confirmed by seeing the top hits for a web search for “*色的旗袍” or “*色的汽车”, which returns mostly results for 蓝色.

| Word | Google hits | Separated Word | Google hits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 蓝色 | 395,000,000 | 蓝 色 | 393,000,000 (99.5%) |

| 黄色 | 331,000,000 | 黄 色 | 1,220,000 (0.4%) |

| 绿色 | 526,000,000 | 绿 色 | 515,000 (0.1%) |

| 白色 | 512,000,000 | 白 色 | 847,000 (0.2%) |

| 黑色 | 570,000,000 | 黑 色 | 941,000 (0.2%) |

| 红色 | 442,000,000 | 红 色 | 794,000 (0.2%) |

1 Some of the 白天“鹅” may actually be mistakes, as in 丑小“鸭”和白天“鹅”.

2 It also returns results for the literal string “char *”, which is very common in C and C++ code.

3 The ratio of simplified to traditional words increases dramatically after 1950, and in recent decades is around 100:1 to 200:1. This is a much higher amount than the 5:1 to 10:1 ratio commonly seen with Google search hits, or with Google Trends graphs. Thus, the Google Book data used by the N-Gram Viewer represents a different corpus than the web content crawled by Search, with a different sampling of simplified vs. traditional texts.

Wow this is immensely fascinating.

I’ve never really thought about how Google treats Chinese searches. Thanks for the research. Very insightful!

I’m totally gonna use that measure word trick in the future.

Keep up the good posts. Really enjoy it!

Another Google N-Gram Viewer hazard to watch out for: OCR errors in the digitized texts! I believe there are more than a few of those.

I have used Google Books to demonstrate that certain words were in use at least 20 years ago (say) and were not (for example) recent imports from Japan. You can also see, in some cases, that the meaning of a Chinese word appears to have changed over time, by searching for it in Google Books over different time spans. (e.g. 色魔)